1954 Grouse Mountain USAF F-86 Crash

Sources: Vancouver Sun, Vancouver Province and Tacoma News Tribune newspaper archives

Second Lt. Lamar J. Barlow pilot of F-86 which crashed on Grouse Mountain in North Vancouver, BC

Second Lt. Lamar J. Barlow pilot of F-86 which crashed on Grouse Mountain in North Vancouver, BCOn February 12, 1954, a USAF pilot flying an F86 Sabre crashed his jet into the side of Grouse Mountain above North Vancouver, British Columbia. The pilot had earlier departed from his home base at McChord Air Force Base in Tacoma, Washington. The F86, which was fully armed with 24 rockets, was reported as taking off on a routine instrument training flight at 10:25 AM. The first word of trouble came from pilot 2nd Lt. Lamar Barlow when he repeated calls of "May Day 2" on the airmen's international distress signal. The pilot reported his compass had failed and that he himself was lost. At 12:06 PM radar operators at Blaine or McChord located the pilot as flying 60 miles north of Vancouver. By 12:15 PM the radar operators had directed the pilot to a position about 15 miles north of Vancouver. Because the plane was by this time very low on fuel, the pilot requested to make an emergency landing. The Sea Island Airport in Vancouver was cleared but radio contact with the pilot was lost before he was given clearance to land.

The weather was overcast and raining so only one witness saw the plane before it crashed. Robin McPherson, the six year old daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Wallace McPherson of 3151 Del Rio Drive in North Vancouver was on her way home from school for lunch, when she the fast flying jet break through the cloud ceiling. At the time she was walking on Queens near the foot of Del Rio. The plane zoomed up and went into the trees on the mountain. She never heard the sound of the crash.

F-86 Takes off from McChord AFB, WA (December 1953) Photo supplied by F-86 historian Duncan Curtis (see f-86.tripod.com)

F-86 Takes off from McChord AFB, WA (December 1953) Photo supplied by F-86 historian Duncan Curtis (see f-86.tripod.com) F-86D 465th FIS, McChord AFB

Lamar's F-86D was Ser. No. 51-2987 - Photo supplied by Duncan Curtis

F-86D 465th FIS, McChord AFB

Lamar's F-86D was Ser. No. 51-2987 - Photo supplied by Duncan CurtisThe last radio transmission from the pilot was that he was experiencing total instrument failure. The jet was flying in a northerly direction with a estimated velocity exceeding 760 mph when it plowed into the trees and mountain at the 2700 foot elevation, near a cabin located a few hundred feet from the ski chair lift. A 1000 foot swath was cut through the trees and wreckage was strewn over a wide area. The crash killed the pilot who was still strapped in his seat.

Two days later, newspapers reported that the fault of the crash was thought to be a "radar ghost". Major Craig Fairburn, head of a twelve man USAF investigation team, said radar operators probably mistook the ghost or echo for Barlow's jet. It was speculated the pilot was probably responding with instructions based on the position of the radar echo when he plowed into the mountain.

The crash site was roped off and protected by armed guards until most of the 24 rockets could be retrieved.

After reading these reports, I had several questions:

Why was the pilot flying 60 miles north of Vancouver when he was lost? Logically, USAF radar operators at the pilot's home field would have been following his flight. Was it normal for USAF pilots to fly far into Canadian territory during a routine training mission? Wouldn't the pilot have multiple redundant instruments to check to make sure he was flying on a correct flight path? Wouldn't the radar station have detected that the pilot had left US air space and was far off his intended flight path, long before he was in danger of running out of fuel for his return flight to home base?

Why was the jet armed with 24 rockets on an instrument training mission? The fact that the jet was armed implies to me that it was either on an air defense mission or a weapons training mission of some sort.

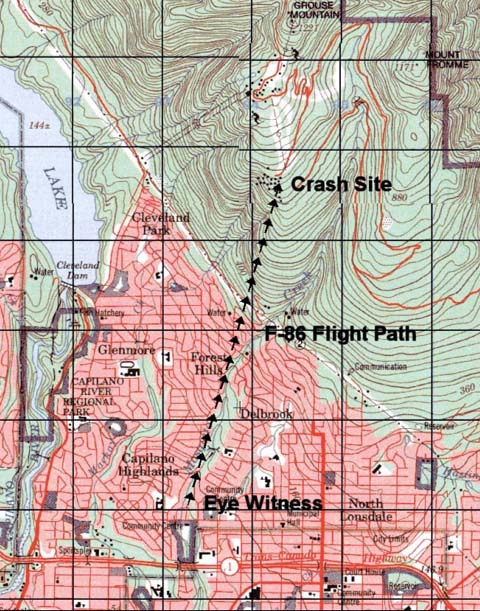

Map of Approximate F-86 Flight Path

Map of Approximate F-86 Flight Path It is of some peculiarity that the plane experienced first a compass failure followed later by total instrument failure. It is also a quite peculiar coincidence that a phantom "radar echo" was sited as a contributing cause to the crash. At this time, UFOs were often explained as "phantom radar echos" by the US Air Force. Encounters between UFOs and aircraft often leads to instrument malfunctions and failures.

It seems apparent to me that one possibility that might explain the incident would be that the aircraft was on a UFO intercept mission. If so, it can be understood that the Air Force would by its own regulations be required to cover up the purpose of the mission.

This would explain why the aircraft was armed. This might also explain why the aircraft penetrated far into Canadian air space during a pursuit. This might also explain multiple instrument failures (possibly caused my proximity of the aircraft to a strong electo-magnetic field) and the "radar ghost" (the real radar return from the bogie).

One mystery is that the real F86 radar return should have been showing an IFF identification code. This should make it easy for the radar operator to distinguish the F86 from a real ghost echo or UFO, unless the IFF signal transmission had also malfunctioned.

Similarly, it is conceivable that the radar operators lost contact with the pilot due to temporary radio malfunctions although no such malfunctions were mentioned. Which makes more sense? The radar operators ignored the jet flying off into Canadian airspace until the pilot suddenly realizes he has only 30 minutes of fuel and has no clue about his position OR the radar operators guided the pilot in pursuit of a UFO into Canadian air space, beyond the farthest distance to return to base thinking the pilot would be able to land safely at Vancouver if he ran low on fuel – the only problem arising when the pilot experienced multiple instrument failures as he was being guided into Sea Island Airport in Vancouver for his emergency landing.

One intriguing detail in the news reports was that most of the 24 rockets were recovered but that a few were still missing. And why was the jet flying at the speed of sound when all logic suggests it should have been flying at a low speed for its emergency landing approach?

Newspaper Articles

CRASHED AT SONIC SPEED

Radar "Ghost in Sky" Led Pilot Into Grouse Mountain

United States Air Force investigators today reported a radar "ghost" led the pilot of a supersonic F-86 Sabre jet to believe that he was over Tacoma and not Vancouver when his craft slammed into Grouse Mountain at the speed of sound on Friday.

The tragic error was revealed by the examination of a group of investigators who spent Saturday combing the twisted, scattered wreckage in which Lieutenant Lamar J. Barlow, 25, of Tacoma, met instant death.

Major Craig Fairburn, head of the 12-man team, said in Tacoma today that investigation was continuing.

Fairburn's party returned to McChord Field with Barlow's remains Saturday night and a maintenance team arrived here today to begin picking up and crating the wreckage for shipment to McChord for study.

Major Fairburn said radar operators probably mistook the "ghost'" or echo, for Barlow's jet fighter. Barlow was following directions being given for this echo when he splattered the mountainside with wreckage after hitting at a speed estimated at more than 760 miles an hour.

Radar experts described the radar echo as being much the same as a television "ghost." It is quite common in the Pacific Northwest.

Captain R. A. Bins said he believed Barlow had been flying at the speed of sound when his F-86 hit the mountain.

Captain R. Allison, official investigating officer, said that Barlow had radioed he was just breaking through the overcast when he crashed.

"It is hard to understand why he would be travelling so fast while coming in so low," said Allison.

The plane hit the mountain at 2700 feet, about 200 feet below the cloud layer.

Major Fairburn said the 25-year-old pilot was "fairly inexperienced" at flying the super-sonic F-86 fighter.

Fairburn agreed with Captain Allison and Bins who said Barlow should have bailed out rather than try to bring his plane in without instruments.

"His electronic commpass which enabled him to navigate blind was out of order," said Fairburn.

"When the radar station picked him up he figured he could come in safely on their instructions.

"Experienced pilots usually listen to what radar operators have to say, then use the knowledge as best they can.

"What we believe Barlow did, was trust completely in the information being relayed to him. He probably thought he was over Tacoma," the major said.

Lieutenant Barlow radioed his base Friday morning that the compass had failed and that he was lost. Radar operators then picked up his image on their screen at McChord and also on the secret radar near the border.

NOTHING SECRET

They directed the image for about 15 minutes before the fatal echo appeared on the screen, the Army official said.

Major Fairburn said contrary to other reports, their was nothing secret about the equipment destroyed in the crash.

"We were worried only about explosives," he said explaining the heavy guard which was placed over the wreck.

"There were 24 rockets on the plane when it crashed, each with the destructive equivalent of a 250-pund bomb," he said.

The major added that none of the explosives could be set off except with electronic devices. He said "nearly all" of the rockets have been recovered.

American medical officers removed pieces of the pilot's body from the wreck as dusk fell over the mountain Saturday.

F86 Wreckage on Grouse Mountain, Feb. 15, 1954

Scattered over an area of 300 yards was shattered wreckage of U.S. Air Force F-86 Sabre after it smashed into Grouse Mountain near chair lift Friday bringing instant death to pilot Lt. Lamar Barlow of Tacoma. This is remains of powerful motor which propelled the jet fighter at a speed greater than sound. Investigators report that faulty radar was responsible for crash - George Diack photo.

Girl, 6, Was Only Witness to U.S. Fighter Crash

Only eye witness to the plunge of a Sabrejet into Grouse Mountain Friday was a 6-year-old girl, it was revealed today.

Robin said today that she was on Queens, near the foot of Del Rio drive, North Vancouver, which is in almost a direct line with the ski-lift track narrowly missed by the plane.

It was just before 12:15 p.m., as she was going home for lunch.

"It was awful low when it came out of the clouds, and it was going very fast," she said.

"Then it sort of zoomed up and went in the trees on the side of the mountain. I didn't hear any noise like a bang."

Investigating officers who returned to McChord Air Force Base, Wash., after probing the speed-of-sound death crash of Lieut. Lamar J. Barlow, 25, said he was flying "blind as a bat".

His instruments had given out, and at 20,000 feet, he did not know whether he was making an emergency approach at McChord or Sea Island.

"In such circumstances, a pilot would usually bail out," said one of the team.

Barlow had not attempted to do this, officers said.

USAF personnel were digging a hole at the scene today to bury the remains of the plane.

They were alos trying to find the last 24 rockets the plane was carrying. Each has the explosive power of a 250-pund bomb. Though they are normally fired electrically, said a technician, some armaments experts consider them dangerous when handled.

All but a few were found Saturday.

Tragic Error Led Jet Pilot To Death on Grouse Mt.

Flier Thought He Was Over Tacoma

Investigators said today they believe a U.S. pilot thought he was over Tacoma when he eased through a murky overcast and smashed his fully-armed Sabre jet aircraft on the 2700-foot level of Grouse Mountain Friday.

This explanation of the crash was advanced by Maj. Craig Fairbun, head of an investigating team which arrived from the Sabre's home base at McChord Field, outside of Tacoma.

Major Fairbun reported that the pilot's electronic compass was defective and he was hopelessly lost in the overcast which shrouded the lower mainland Friday.

The pilot was being guided from McChord Field and Blaine and although he was talking with the Blaine station, may have thought he was on the McChord beam.

"He knew he was over either Vancouver or Tacoma and may have thought it was Tacoma," Maj. Fairbun explained.

DANGEROUS ROCKETS

The wreckage will be under strict security guard until detonating teams explode or defuse the cannon-type rockets which the plane carried.

Maj. Fairbun said, "We will try to remove the entire wreckage to our base, and what we can't move, we will bury."

The wreckage, discovered by a young skier about 8:30 p.m. Friday, was strewn over a large area about 200 feet from the Grouse Mountain Chair Lift.

Twenty-four-year-old Ray Nunn, 2490 West Thirty-seventh, found parts of the crashed plane scattered over the area immediately behind his cabin at the seventeeth tower of the Grouse Mountain Chair Lift.

Main body of the crash lay smashed and splintered within 15 feet of Nunn's cabin, the "Doghouse," about 100 yards east of the chair lift and one mile from the ski village.

Jagged metal and ripped fabric was spewed for hundreds of feet around, a parachute ripped open by the impact dangled from a tree. There was no sign of fire.

MAY DAY CALL

Barlow, of Tacoma, had taken off from McChord Field on a routine training mission when he ran into instrument trouble 60 miles north of Vancouver.

First word of trouble came from Barlow with repeated calls of "May Day 2," the airmen's international distress signal. At 10:25 the lost and confused pilot's plane was picked up on radar at Blaine and directed to Vancouver.

15 MINUTES FUEL

At 12:15 noon with less than 15 minutes fuel left in his tanks, Barlow radioed Blaine asking for permission to make an emergency landing. By this time, the Blaine radio station had directed him to a point 15 miles north of Vancouver.

The young pilot went off the air at 12:16 noon. He said he was going down through the overcast to land.

Barlow was flying with the 465th Fighter Interceptor Squadron.

Neither his mother, Mrs. Letta May Staples, of Richfield, Utah, nor his wife in Tacoma were notified of his death until about 8 a.m. today.

INVESTIGATORS DUE

American Army officials at McChord Field said the young pilot's home town was Richfield but he had taken up residence at Tacoma after being stationed at McChord.

Nunn, an enthusiastic skier and member of the Grouse Mountain Ski Patrol, said he found the wreckage when he arrived at his cabin for the weekend.

SMELLED GAS

The young apprentice electrician said he had left the chair lift at the chalet and climbed down the mile to the cabin. Entering the cabin from the rear, he said he smelled gasoline and saw pieces of metal lying in the snow.

"I'd heard a plane was missing," he said. "I knew what this was as soon as I saw it."

Nunn picked up a sheaf of official papers from the snow and later turned them over to the Royal Canadian Air Force.

The plane, heard by many North Shore residents as it whined low overhead at noon Friday, smashed into the mountain shortly after it was last heard from at 12:04 p.m. and sheared a wide swath through the thick brush.

HIT WINDOW

One flying piece of metal smashed through a window at the rear of Nunn's cabin.

After his discovery, Nunn sought the help of three friends living close by in the "Al Ron" cabin who helped him search through the wreckage. Unable to find the pilot's body, the men returned to their cabin. Nunn said about 9:30 p.m. he stopped two girls hiking up the ski trail to the chalet. He told them to notify the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and RCAF search and rescue officials.

RCAF at Sea Island said they were notified of the discovery shortly before 10 p.m. They immediately organized a ground search party.

11-MAN PARTY

The 11-man party, led by Sergeant Red Jamieson, of the RCAF Rescue Flight, left North Vancouver RCMP office at 1 a.m. Saturday.

Discovery of the pilot's remains was made about 2 a.m. by Constable Al Clark of the RCMP. Body was found close to the main part of the wreckage behind the cabin.

Constable Clark said it appeared as though the pilot was still strapped into his harness and had made no effort to abandon the plane as it roared into the mountainside.

"Its hard to tell though," he said.

Const. Clark, Constable Alex Link, Sgt. Jamieson and two other RCAF searchers toured the area with powerful flashlights.

WRECKAGE GUARDED

The wreckage was mainly in small pieces, about the size of a man's arm, although Const. Link reported finding the plane's landing gear and a four foot section of fuselage with a white star on it.

Other searchers included LAC Fred Tavernor, LAC Andy Valis, and Vancouver newsmen.

The three RCAF men immediately set up armed guard over the area and plans were made to cordon it off until an air force investigation team reaches the site.

In his last message, the pilot said he was flying due west, 15 miles north of Vancouver at a height of 20,000 feet. The message was immediately relayed to Vancouver Airport control tower.

An aerial search by four RCAF planes had to be abandoned after three hours at 5 p.m. Friday becauce of bad visibility.

The planes, led by Squadron Leader William Fee, officer commanding Rescue Flight, scoured a 500-mile wide area and were scheduled to go up again for a more intensive search.

Although no one was reported to have heard the plane crash into the mountain, RCAF and RCAP say they were swamped with calls from North Vancouver residents who said they heard a jet flying low over the North Shore about noon Friday.

One man, John Skog, 1601 East Third, a carpenter, told The Sun he was working on a house on Prospect Avenue, North Vancouver, when he heard what sounded like the stalling of a plane's motor overhead.

"I heard a jet fly over just about noon," he said, "and the it stopped. I didn't hear any crash. Nothing but silence."

This is the second jet airplane to crash in the Grouse Mountain area.

Probe Opens In Top-Secret Jet Crash

Latest Equipment Aboard Lost Fighter

Province Reporter Locates Body On Mountain

By Paddy Sherman

U.S. Air Force officers today began probing the wreckage of an F-86 Sabre jet fighter, loaded with "top secret equipment," which crashed on Grouse Mountain Friday afternoon, strewing parts hundreds of feet and fatally injuring its pilot.

The whole of the Grouse Mountain area was temporarily sealed off this morning to prevent skiers from tampering with the wreckage. RCMP took 1000 feet of rope up the mountain this morning to cordon off hte area.

Grouse Mountain Ski Lift operation will be normal however.

The Sabre, from McChord Air Force Base, carved a 100-foot swath of devastation as it plowed into the mountainside at the 2500-foot level and disintegrated.

I found the body of Pilot Lieut. Lamar J. Barlow, aged 25, of Tacoma, 50 feet from one of the best known cabins in the mountain - the vivid green and yellow Dog House at Tower 17.

This was at 2:30 a.m., and ended speculation that the pilot had managed to bail out by using his explosive charged ejector seat.

Barlow is survived by his wife, Gloria Jane of 10103 Kline street, Tacoma, and his mother, Mrs. Letta May Staples, at Richfield, Utah, Barlow's home town. They were notified of his death at 8 o'clock this morning.

Barlow had been at McChord field since October.

The plane had apparently hit the mountainside while dropping in low to make an emergency landing at Sea Island. It was travelling north.

A rain of pieces, some of them no bigger than confetti, peppered the cabin, smashing a window. No one was inside at the time.

Other parts flew over the lift track, littering the snow. The lift was not running at the time.

The North Vancouver coroner's office announced today it will not schedule an inquest or inquiry into the crash.

KEEPING WATCH

Today, Sgt. J. R. (Red) Jamieson and two armed guards were keeping watch on the roped off area until Major Craig H. Fairburn and a team of investigators could reach the scene.

The young pilot never had a chance after he radioed that all of his instruments had failed when he was at 20,000 feet, and 15 miles north of Vancouver.

When I found the pilot, he was still strapped to his seat by the safety jet. His unused parachute fluttered from one of the many trees smashed by the hurtling jet.

HEAVY RAIN

I reported the find to Sgt. Jamieson and RCMP Constable Al Clark, examining wreckage nearby in fog and heavy rain.

The alarm was given by Dog House co-owner Roy Nunn, of 2400 West Thirty-seventh.

"I went to the cabin about 8:30 p.m. and walked over to check on the outside water line.

"Pieces of wreckage were littered around. Just then, two girls passed, hiking up the track, and I gave them numbers from part of the wreck. They telephoned RCMP.

NORTH OF CITY

Last contact U.S. airforce base at McChord Field had with Barlow's F86 jet was at 12:0? when the pilot radioed he had "lost" his instruments.

Radar placed his position as being 60 miles north of Vancouver and guided him to within 15 miles north of the city.

Major C. D. Sawfelle, public information officer of the 25th Air Division of the U.S. Air Force, said at that time, the pilot radioed "Mayday" - an SOS indicating, "that he had lost his instruments and that he himself was lost."

CLOSER TO CITY

The U.S. Air Force radar station at Blaine picked up the plane and guided it closer to Vancouver where the pilot requested permission to make an emergency landing.

RCAF officials here say that after receiving the emergency call, about 12:06, the airport was cleared, but when the airport tried to reach Barlow by radio, to tell him to come in, no contact could be established.

OVER TELEVISION

As soon as radio and radar contact with the ill-fated plane was lost, U.S. Air Force contacted radio and television stations, asking them to broadcast emergency bulletins, advising people in the Vancouver area who might have heard a jet plane to contact the McChord air base.

More than 30 residents of the Vancouver area phoned the McChord base and other calls flooded into the RCAF operations centre here.

Major Sawtelle assured The Province that these calls were "an immense help." "The calls narrowed the search area down," he said, "and assisted us greatly."

HOME FOR LUNCH

One of the calls to RCAF headquarters came from C.V. Clee of 224 West St. James road near the foot of Grouse Mountain.

"I just happened to be home for lunch," said Mr. Clee, who installs meters for the B.C. Electric, and was working on the North Shore Friday morning.

"About noon we heard this sudden roar-it just seemed to be over the house and it sounded like it was a plane in a steep dive."

FEW SECONDS

"The roar lasted for a few seconds and then faded out completely.

"Later we heard a Seattle radio newscast, telling of the crash and advising Vancouver residents to contact McChord field.

"We didn't do that but we telephoned the air force here."

The roar lasted just about 30 seconds, Mr. Clee said. He added that because of the rain, he and his wife couldn't see any plane, or know in which direction it was travelling.

Another call to McChord Field, helped to isolate the crash area even more.

Major Sawtelle said one Vancouver resident called to say that he had heard a jet plane in the North Vancouver area.

The plane seemed to be circling, the caller said, then sounded as though it was headed on a straight course. The roar of the engine didn't fade - it stopped suddenly, indicating that it had either crashed or gone behind a mountain, Major Sawtelle said.

CIRCLED CITY

After radioing the airport here, it is quite possible the pilot skirted the perimeter of Vancouver in an effort to avoid crashing into the city proper where he would be endangering the lives of unsuspecting people. This could account for his crashing into the North Shore mountain, said Major Sawtelle.

"However, all our boys are instructed to jump by parachute if they get into a tight spot," said the major.

STAY WITH IT

"However if he knew he might kill many other people if he left his plane, he would decide to stick with it."

Speed of the plane at the time of the crash is hard to estimate. Barlow was short of fuel - he had only enough to last to 12:30 or 12:45 at the latest.

He would be trying to conserve his dwindling supply, hoping for the emergency landing at the airport.

AT 200 MPH

McChord base experts say he would probably be travelling atbout 200 miles per hour at the time of the crash. An F-86 Sabre jet can go better than 600 knots an hour.

U.S. Air Force officials say Barlow was a fully-experienced and "combat-ready" jet pilot.

They also add the plane was in "sound condition."

ROUTINE FLIGHT

Barlow took off from McChord on a routine instrument training flight at 10:25 a.m. on Friday.

As soon as the plane was officially "lost," the finely-tuned machinery of the RCAF swung into action.

Four RCAF planes - two Expeditors, one Canso flying boat and an Otter-a light reconnaisance plane-were sent into the air about 1:30 under the command of search master Squadron-Leader W. M. Fee.

They scourder North Vancouver and the area around the Straits of Georgia.

They covered the area from Lasqueti Island to Point Roberts, said the air officials.

Heavy weather hampered the search and finally forced the planes to return to Sea Island between 4 and 5 p.m.

Also taking part in the search was a Grumman Albatross from McChord Field - an amphibious plane which searched the waters surrounding the area.

All boats in the area were notified.